Supporting Graduate Students' Academic and Professional Success

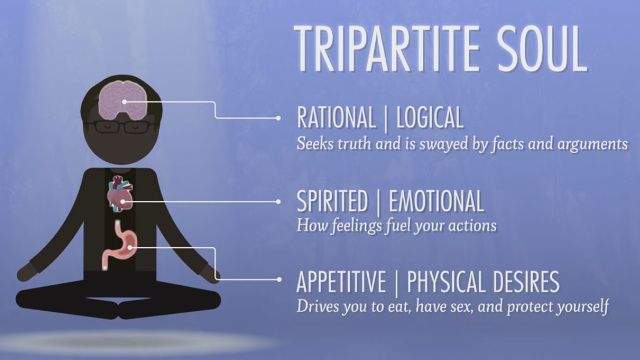

Education has long been considered of paramount importance when it comes to achieving social justice. While modern-day learning institutions have increasingly supported social justice by empowering students and actively engaging with discourses surrounding issues of systemic injustice, the relationship between education and social justice has been acknowledged since ancient times, tracing its origin in the West back to Plato’s Republic. In the Republic, Plato distinguishes social justice from individual justice. Social justice is the condition of a society that is well ordered, embodying a functional unity among a philosophically enlightened ruling class, a guardian or military class, and a goods-producing merchant class, as well as between the individual citizens that comprise these classes. Individual justice is the condition of a well-ordered, harmonious soul. According to Plato, the soul is an intrapersonal unity comprised of a rational part, a “spirited” part that executes the demands of reason, and an appetitive part. These parts of the soul correspond to the three classes of the state. The soul is harmoniously ordered when the parts inhabit their proper place in a hierarchy, much like the state is harmoniously ordered when classes are functioning properly in their position within a unified political whole. The well ordered state demands that the souls of its citizens are similarly well ordered, since having a harmoniously organized soul allows individuals to exhibit virtue or excellence in their prescribed social roles. And having a well ordered soul is the desideratum of education: one perfects the rational part of the soul by testing it within an educational process designed to promote the rational part to its rightful place as leader, thereby achieving harmony among the three parts.

[Image Description: The figure depicts the three components that Plato thought comprised the human soul, with one arrow pointing to the brain labuled 'rational/logical: seeks truth and is swayed by facts and arguments, a second arrow pointing to the heart labuled 'spirited/emotional': how feelings fuel your actions, and a third addor pointing to the gut labuled 'appetitive/physical desires': drives you to eat, have sex, and protect yourself.]

Pictured: The three aspects of the soul that Plato saw as needing alignment in order to achieve individual justice.

Even if Plato’s substantive picture of the just society as a socially stratified aristocracy is objectionable from a modern, more egalitarian perspective, perhaps this perspective is nonetheless compatible with Plato’s view that social justice (in some form or another) is to be achieved through individual justice, and that individual justice is to be achieved through education. If Plato is right, then a commitment to social justice on the part of educators demands that priority be given to students’ education as a matter of individual justice. However, this requirement turns out to be essential for Plato in a way that it is not essential for we moderns. Modern notions of justice differ markedly from those of the ancient Greeks not just in their substantive representations of a just society but also in their interpretation of justice itself. Ancient Greek notions of justice are associated with unity, harmony, and healthy functioning. Being just implies being well ordered. For Plato, this holds true for both individuals and society. By contrast, the modern conception of social justice centers specifically on ideals not of harmony but of emancipation, equity, and enfranchisement. It also leaves out any explicit connection to the sort of (specific, substantive) understanding of individual justice (i.e. as intrapersonal unity) that Plato defends. Thus, the modern conception of social justice seems to disregard the tight connection to individual justice that Plato envisioned.

[Image Description: Roman mosaic of the 1st century BCE from Pompeii, now at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, depicting Plato positioned with other philosophers, pointing at a globe with a stick]

Pictured: Plato engaged in educating others within a social learning environment

What sense, if any, might be made of individual justice from a modern perspective? The foregoing description of the modern conception of social justice favors a pessimistic response. The concept of individual justice—as a necessary condition of social justice, at least—seems to fall by the wayside with the arrival of modern notions of justice. If educators have a role to play in preparing students to participate in a just social order, they play this role by engaging in discourses surrounding social injustice, not necessarily by directly facilitating students’ self-unification. This is not to say that the educators within the modern perspective undervalue the personal growth of their students. However, from a modern perspective, the value of such growth consists not in achieving something we would call individual justice but in helping students solve problems and participate as functional economic players. From this perspective, the value of self-unification for students as individuals is mostly instrumental, whereas justice purports to be valuable for its own sake.

[Image Description: A man opens a book, revealing a light shining forth from the text]

Pictured: The transformative power of education for the individual

Even where something like self-unification or self-actualization is the explicit goal of an education plan, it is not typically conceptualized as a matter of individual justice per se. If students’ personal growth (or the opportunity to pursue it) is seen as a matter of justice, it is more likely seen as a matter of what people are owed within an equitable social order as such, not a matter of some internal property of the self. The very idea of individual justice remains stubbornly haphazard from a modern perspective, it seems. And this appears to stem from the fact that, unlike Plato’s conception, the modern conception of social justice does not contain a specific, substantive conception of the just social order in terms of which it understands the justly constituted self. Social justice from a modern perspective is more focused on critically targeting structural inequities than on instantiating a specific version of the ideal political state. But the notion of inequity is relegated to the realm of interpersonal (and not intrapersonal) relations in a way that the notion of disunity is not. Consider how elusive a notion of intrapersonal inequity seems when contrasted with the idea of (relative) intrapersonal disunity: the latter is readily grasped in terms of the mundane internal conflicts one can experience between one’s ordinary values, desires or beliefs, whereas the former reads like a category mistake. Absent a plausible idea about what structural inequity amounts to when construed as an internal property of an individuated person or mind, the notion of individual justice remains disconnected from social justice from a modern perspective.

[Image Description: A teacher from, Inside Out, smiles at her students from the front of the classroom. The image zooms in to show us the personified images of her internal feelings.]

Pictured: A modern interpretation of the internal self

I have so far been questioning the relevance of Plato’s conception of individual justice for educators committed to (a modern ideal of) social justice. The notion of individual justice seems particularly obscure from a modern point of view. Despite this, I suspect that the concept of individual justice can be made useful for modern educators willing to take it seriously. Social justice in a modern context consists, inter alia, in a critique of society’s values, practices, and institutions. In a world subject to sustained critique, students must be afforded the opportunity to develop a pliable, critical competence, in order to be able to evaluate new ideas in a potentially ever-evolving cultural context. Accordingly, students must be encouraged to develop such a competence by critically self-reflecting on their own values, actions, and beliefs, much the same as social critique reflects on society’s values, practices, and institutions. Social critique aims at a responsibly organized society; critical self-reflection is a means of taking responsibility for one’s knowledge. Critical self-reflection might thus be called a modern form of individual justice, reinforcing the relevance of Plato’s link between individual and social justice for modern educators.