Supporting Graduate Students' Academic and Professional Success

Have you ever found yourself in a staring contest with an assignment after 10:30 PM that goes on for an absurd amount of time? Does the amount of grading work that awaits you in the coming finals week make you feel awful? If yes, then you are not alone. Grading can, and frequently does, consume the most significant amount of our TA hours and puts a dent in our productivity in our research or graduate coursework. So how do we make this mammoth task a little bit more manageable? Well, The Teaching Assistant Development Program (TADP) is here again with strategies on how to grade student work in ways that maintain fair and accurate standards, as well as your sanity.

[Image Description: Sitting on a desk in an office, Robert E. Blackmon stamps on a paper as he tilts his head and nonchalantly stores the page in an office organizer when he finishes]

Pictured: Stamping ‘C+’ on every paper is not one of the TADP-recommended grading methods.

Before You Begin

Effective grading takes so much time because providing personalized feedback is a highly time-consuming task and can be a significant drain on an instructor’s time. Still, many times students tend not to read the comments. They look at the grade and get on with life. As a result, the same mistakes occur in subsequent assignments or finals. Feedback should also be given fast. If a student waits too long for feedback, they risk losing the context for the valued instruction of the week. Therefore, to positively impact students’ learning, we must give concise customized feedback within at least seven to ten days after a student submits the work. Assignments also come in many different forms: quizzes, tests, homework, short papers or writing prompts, long essays or term papers, projects, presentations, etc., which all bring their unique challenges of grading with them. Therefore, before you begin grading:

1. Meet with the professor to discuss course grading policies. It is possible to save a lot of time by discouraging redundant regrade requests or requests that make you grade late work. Also, think about any questions to ask about what to do if you encounter strange cases in student assignments. Some of the example questions could be-

- If they add irrelevant information- do you take points off?

- Should you stop reading at the page limit?

- What is the breakdown of partial credit?

In a nutshell, you don’t want to worry about things you do not need to.

2. Make sure to go over the assignment design and all the requirements with your professors. If the assignment is clearly worded and explicitly tied to clear learning objectives, grading them is more straightforward.

- Ensure that you have all the material components you need for grading (e.g., access to iLearn/eLearn, rubrics if you’re attaching them, the actual assignments).

- If you have created the questions, make sure the professor vetted them before the test.

- Determine where and how you need to store the grades. Whether you are grading physical copies of assignments or online tests, you should always securely store the grades in the learning management system (iLearn/eLearn) in compliance with FERPA policies.

Give yourself a few days to do the grading if possible; rushed grading is sloppy grading. Meanwhile, it doesn’t hurt to have other TAs of the same class in the loop to compare their class averages with yours.

While You Are Grading

Always use a rubric

First, you must decide precisely how you are going to grade. With multiple-choice tests or mathematical assignments, there’s a straight right and wrong answer. Things get a bit vague with papers, and it can be hard to figure out the difference between an A paper and a B paper. To avoid this problem, be sure to get a clear rubric before starting to grade. Your instructor might have one but, if they don’t, you can always use the general guidelines your instructor gives in the syllabus, create one of your own and stick to it. Having a well-defined rubric before you set out prevents your grading standards from shifting as you go along.

A rubric is a rational set of criteria that describes the levels of performance quality for students’ work. When created and used correctly, a rubric is the most excellent grading tool to support and strengthen instruction and learning. There are two types of rubrics.

Holistic: In this type, all criteria are lumped together and evaluated simultaneously, making it faster to create and grade.

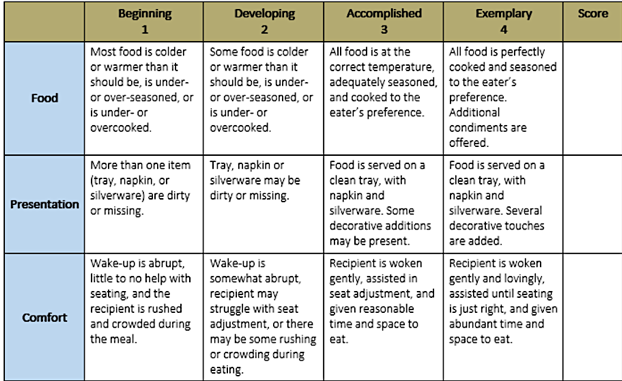

Analytic: An analytic rubric evaluates each criterion separately, which gives specific feedback to the teacher and student about performance. The analytic rubric is the preferred rubric type of most instructors as it holds a clear record of areas in which students lost points. It has three parts:

- Criteria: The list of components used to evaluate an assignment that provides explicit expectations for the performance. In our example, the three criteria are food, presentation, and comfort.

- Levels: These are the rating system used to evaluate the quality of the criteria for students’ performance. Our example is a scale of 1-4, starting with beginner and exemplary at the highest level.

- Level description: The detailed description of a student’s performance at each level gives the score for each criterion. Our example contains these descriptions in each of the requirements and level boxes, like “tray, napkin or silverware may be dirty or missing.”

[Image Description: Example of an analytic rubric that describes the criteria, levels, and level description of an assignment “Breakfast in Bed.” Adopted from Brookhart, S. M. (2013). How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.]

Pictured: An analytic rubric, all yours to adapt and change

[Image Description: Gandalf, as he stands before the Balrog in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, says with conviction and rage, “You shall not pass” as he raises his sword and staff together in the air and drives them into the bridge]

Pictured: You after grading that 30th paper, the writer of which obviously had no clue but gave a try anyways

Managing time for grading is important

Expert educators will tell you ungraded papers are just like laundry. If neglected each day for a week, the laundry will pile up. The same applies to assignments. If you grade a small fraction of the total material to grade each day, you will manage to keep the workload reasonable. To begin small, you can aim to grade for 30 minutes each day, and when you accomplish that goal, you will see your efforts have accumulated to keep you on the right path. As we discussed earlier, it is advantageous for students to receive feedback quickly after submitting a task when the material or skill we graded them for is still recent in their minds. Here’s what you can do

Divide and conquer: Dividing the assignments into manageable chunks makes them more approachable. You need to decide how many tests/papers you can assess in one sitting without compromising the quality of the feedback. You can make stacks based on the number (8 tests at a time) or percentage (1/4th of the total tests). If I am grading numerical problems, I grade one question at a time, like all number 1s and then all number 2s. If I am grading essays or term papers, I grade them individually.

Grade with a timer: This strategy sustains focus and eliminates the temptation to write very detailed feedback. I tend to grade most of the time with the Pomodoro technique.

- Pomodoro technique is a time management method developed by university student Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980s. This method would use a timer to break down the task into intervals, usually in 25 minutes blocks, separated by short breaks. Each block is known as a Pomodoro, from the Italian word for ‘tomato,’ after the tomato-shaped kitchen timer that Cirillo used.

Here’s how I use it: Suppose I have 40 worksheets to grade. I set the Pomodoro for 25 minutes and make a small oath to myself that I will not interrupt myself, will not check texts or news. Based on the rubric and the assignment, I determine how much time each work will take to grade. Then I immerse myself in the task for the next 25 minutes. I ensure that I am sticking to the determined time per worksheet. I also maintain a running list of common errors I am encountering so that rather than writing the feedback on each worksheet, I can discuss the mistakes with the whole class

[Image Description: Lorelai Gilmore, from Gilmore Girls, looks exhausted and says, “I need coffee in an IV” while gesturing to her left arm.]

Pictured: A grad student grading without a break

Provide effective and concise feedback

TAs often make the mistake of starting to edit students’ work rather than providing relevant feedback. One way to make your grading go smoother is to focus on the types of comments you are writing. Too few words and students will get confused about why they got their poor grade, but too many comments and you’ll be grading forever. A good guideline is to write no more than four words per individual error. Grammar mistakes can just get a symbol, like these grammar and editing symbols while something like a flawed argument or a cumbersome paragraph might just get a “check wording.”

- Glow and grow: One widely accepted method of providing effective feedback is the glow and grow, which we can use to write up two comments that summarize one positive (glow) and one negative point (grow) at the end of the assignment. This practice will let students know why they got points deducted and what they did well while saving the TA from writing out a novel’s worth of comments.

- You should always avoid over-commenting and instead focus on patterns, strengths, weaknesses in a presentation, etc.

- It is a recommended practice to go over the shorthand comments you have used with the class.

[Image Description: Andrew Robertson oozes confidence as he tells the interviewer, “I’m in this to win it.”]

Pictured: Your students' confidence about success with your effective feedback

Use technology whenever you can

To ensure fair grading and avoid making biases based on favorites, my philosophy is to do “blind” grading. As we are teaching online for the last several quarters, I rely on either iLearn or eLearn to make anonymous grading possible. Visit the links to the respective pages of BlackBoard and Canvas to find how to set a test for anonymous grading. Also, writing or typing comments is not the only option in today’s world with so many technologies available. Kaizena is a voice comment feedback tool for instructors that is compatible with Google Docs as well. Our very familiar Google Doc has its voice typing option under the Tools, an excellent method to leave voice feedback on student documents when used with appropriate caution. Canned replies can be used to create a set of commonly used input and simply access these from within Gmail or from the context menu and browser popup. Voxer is another free app for using comments for students.

Finally, each of us is unique and teaches different classes with its distinctive grading challenges, so TADP suggests you try and find a routine and adapt to some of the strategies we discussed. Explore what is most effective for you and stick to that to best help your students and yourself.